Some time ago, the President of the Philippines was asked at a Press Conference if she had sex.

She replied that she did and laughingly stated that was what would hog the headlines next day, not what she had spoken on development. I wonder if the President’s sexual needs and fulfillment are of any relevance to the public or to the nation.

Was the question in any way necessary? Did it bear on some vital national or socio-economic issue? No. Was it meant as a touch of humour? Surely, it speaks of a rather dubious sense of humour.

ADVERTISEMENTS:

As far as I could understand, it could not be considered ‘investigative’, at least in the right spirit. But then why was it asked? There can be no satisfactory answer. In the Western world, the sexual peccadilloes of influential people, especially politicians, seem to be of special interest to the media.

Take the case of former Prime Minister of Britain, Mr. Major who quit office with a fairly unbesmirched reputation. But, after quite some time, one Edwina Currie “revealed it all” by publishing her diaries and giving an interview to The Times she hinted that John Major, had an affair with Edwina for four years. It was in the 1980s, in the days of Mrs. Thatcher’s prime minister ship when Major was not a minister.

But he was the Conservative Party whip responsible for discipline which presumably included noting such misdemeanours. For, John Major was, after all, married at the time and as such, guilty of adultery.

ADVERTISEMENTS:

Edwina spilled the beans, Major quietly accepted the charges and merely said that he was ashamed of the episode and that his wife had known of it and had forgiven him.

Quite the stuff of a Mills and Boon novella, except that the figures involved are well known and quite real.

The funny thing about the exposure is that the media did not sensationalise it; indeed. There seemed to be a sneaking admiration for the former Prime Minister—attaboy, quite a chhupa rustam what? All those pious sentiments about ‘back to basics’ involve respect for family and the law and traditional teaching, etc.

And credit for all those self-righteous dismissal of ministers—Tim Yeo, Hartley Booth, Michael Brown—in his council of ministers for sexual scandals associated with their names goes to media.

ADVERTISEMENTS:

So, not morality wins the day, but your ability to hide your immorality from the light of the day, or, shall we say, the media. True Victorian morality of which many of us seem to be so very fond of: appearing to be what you are not; in other words, hypo crispy.

So, why did the media not go to town about it? It could be because media was not instrumental in exposing the affair; it could be that it is not half so much fun, or brutally amusing, as it would have been if the poor man had been in office; if he had been in office, the media could have shown its power by informing the public of the sleeze and working to get a resignation from the Prime Minister and taking the credit of having toppled the government. Ha! The power of the media and investigative journalism! In other words, now the news had no news value.

The thought of what the media would have done if the case had come to light in the days when Major was Prime Minister leads one to wonder whether such invasion of privacy is justified.

Are the sexual peccadilloes of the politicians and other famous people so relevant to national interest that they need to be plastered across the front pages of the national newspapers or exposed on prime TV time? More importantly, is the politician or any other public personality, for that matter, not entitled to a private life?

This is not to condone adultery or sexual perversions, but these may surely be dealt with within the sphere of family and close connections, as they are in anybody else’s case.

Amidst all the adverse publicity that the media thoughtlessly heaps on the culprit, the innocent have to pay a price and suffer for no fault of theirs — the wife who has been treated shabbily, the children of the public figure. How right is it to say the public figure is not entitled to a private life?

Even if one subscribed to the nation that public figures have to be transparent in their actions and their opinions, differentiation has to be made between actions and opinions that impinge upon the public domain and those that are of personal nature.

The line separating the two may be thin in the case of public figures because their lives are so open to scrutiny, but the line, nevertheless, exists and can be sensed.

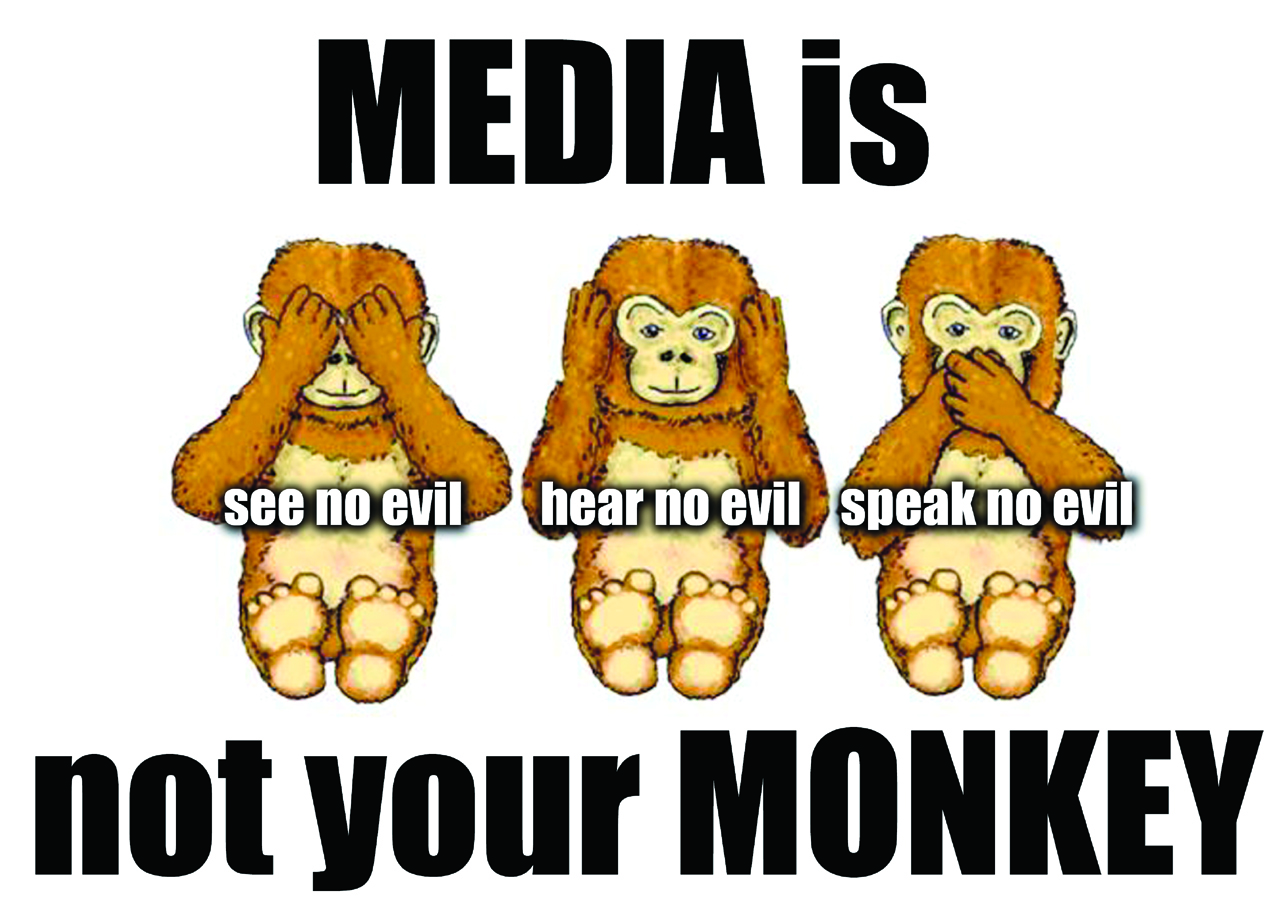

The media is also well aware of this dividing line and has no right to obliterate it. If it does intrude, it is because it knows that the public derives vicarious pleasure from the faults and foibles of the famous and the ‘great’, – a gleeful satisfaction in knowing that those personalities feted by so many and always in the limelight are no better and no worse than the ordinary human being.

And in all this, sexual misdemeanours somehow appear more attractive to a large class of readers and viewers just as sensational crimes do. Exploiting this human weakness may be good business in terms of money, but it is not good media ethics.

True, if the private life of a public personality showed a propensity for activities that could endanger the life or well- being of others or pose a danger to national security and social good, and the media has information-on such activities, the information must be publicised in public interest.

A child abuser or rapist or just one who enjoys sexually harassing a colleague or subordinate in office is, indeed, worse than one in any other walk of life, as he or she can use the power of office to indulge in the crime. It is the media’s duty in such cases to expose the criminal.

But it is no business of the media to chase around after famous personalities to photograph them when they least expect it or to keep up a running commentary on the exploits of their love life—however much a section of the reading public may desire to know about them.

But the Indian media is not as respectful of the privacy of the dead and the injured and the grieving. And this is obvious every time a disaster occurs. In the eagerness to achieve the status of having a ‘breaking story’, the media—especially the electronic media—has shown shocking insensitivity, both to the victim of a disaster and to the viewing public.

Accidents have each channel claiming every ten minutes that it was the one to break the news. Besides, the camera focuses on the dead and the injured with a cruel indifference to the dignity of an individual.

The dead, it seems to proclaim, have not the same rights as the living, and those injured too badly to know what was happening are also second-class citizens forced to give up their right to privacy in the interest of a ‘good story’. As for the viewers, this intrusion manifests the vulnerability of the dead, and the scenes repeated ad nauseam prove distasteful, to put it mildly.

Even in the case of terrorists who are shot, there is no need for the cameras to linger on their bodies: their actions may have been condemnable, but why exhibit their dead bodies lying in the pools of blood?

To satisfy some collective sense of revengeful satisfaction? Close shots of relatives and friends of the dead and injured torn by grief and howling in sorrow, are also an intrusion in the privacy to which every individual as a human being is entitled, more so in a democracy.

Poignant these scenes may be, newsworthy too, but a viewer with even normal sensitivity is left uneasy, shifting uncomfortably and trying to avoid the television screen.